Fighting for civil rights over a lifetime

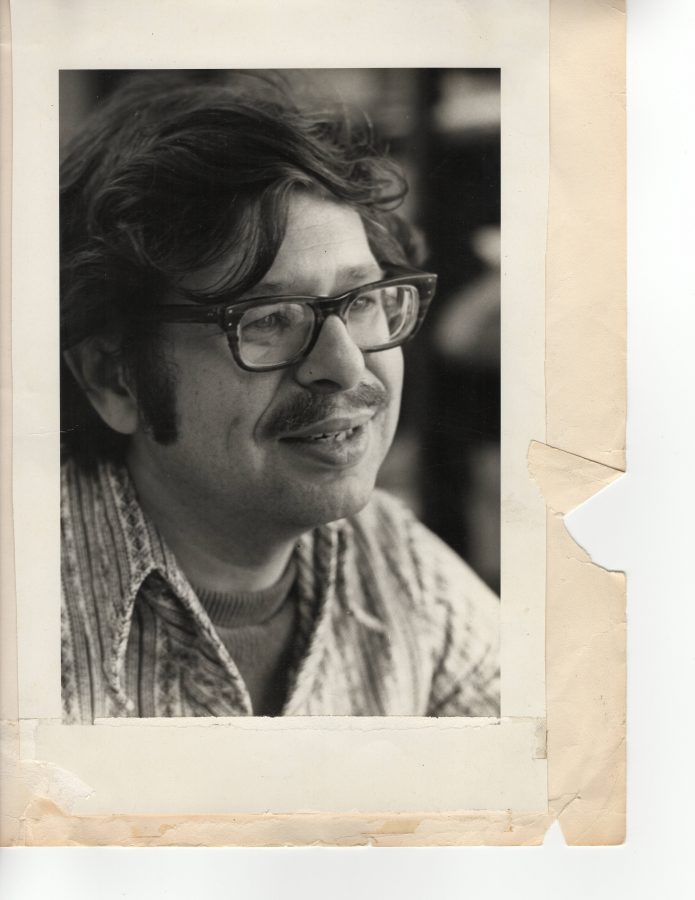

I have family who live in Jackson, Mississippi, and Rims Barber is our next door neighbor. When we go on vacation, he and his wife will sometimes watch our pets. They’re great neighbors; during this interview, they had a plate of cookies sitting on the table. We’ll talk with them often, with our conversations ranging from local events to civil issues and politics.

Even though we have made incredible progress since the time of Jim Crow, civil rights are still very important issues. With the growth of the Black Lives Matter movement and a tumultuous election, these issues have come to the forefront of the minds of American people. There is still progress to be made, and we cannot improve anything without knowing our history. By understanding civil rights, we can understand where we come from and what people have done to improve the world that they live in.

During Freedom Summer, a large-scale event for increasing African American voter turnout in the state of Mississippi, Rims Barber became involved in the Civil Rights Movement in an effort to desegregate schools and to increase African American voter turnout in state and local elections, among other things. Since then, he remains involved in civil rights and Mississippi state politics.

In 1964, civil rights groups like the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) organized Freedom Summer. Volunteers with the project faced consistent harassment, and citizens would often refuse to talk to them. “We’d go knocking, door to door,” Barber said. “But one of the problems was that the police would follow us, and people would peek out through the window and say, ‘Go away; come back some other time. We’ll talk to you, but not with the cops there.’”

Being involved with civil rights at the time was risky. Many people lost jobs or were evicted from their homes. “We took one little girl down to the school, and her mother registered her for first grade in a formerly white school,” Barber said. “By the time she got back home, all her furniture was out in the street. Her landlord had evicted her, because that was the way they evicted you.”

Civil rights activists and workers faced many violent acts. Freedom Houses would be firebombed or shot at, and some activists were even killed. “In 1966, in Philadelphia, Mississippi, I was standing outside the Freedom House in the black part of Philadelphia. We’d had a march that day to commemorate the anniversary of the killing of a civil rights leader,” Barber said. “Someone came driving through, and he emptied his gun out the window in our general direction. He wasn’t much of a shot, but it was scary.”

Progress towards equality was not only occurring in the streets and through organizations like CORE. Change was also happening in the government. When Robert Clark was elected as the first African American member of the Mississippi House of Representatives, Barber was given the assignment from the Delta Ministry of opening an office in Jackson to help Clark. There, they continued to work with schools, among other projects and laws. “I helped draft bills for Mr. Clark to do things like kindergartens and compulsory school attendance, because we didn’t have it then,” Barber said. “They had done away with it after the Brown [v. Board of Education] decision on school desegregation because they didn’t want to force kids to go to school if they ever got desegregated.”

Steps towards equality could also be found in local governments. Elected officials could use their positions to correct old injustices. When Bennie Thompson was elected as the mayor of Bolton, Mississippi, Barber worked with him to correct issues. “One of the first things was there was a fire, and the fire truck wouldn’t start and the hose didn’t have enough pressure, and they couldn’t put out the fire,” Barber said. “What we found out was that the pipes in the black community were about a fourth the size of the pipes in the white community, so there was no way to get pressure out of the fire hydrants in the black part of town.”

Barber has long been involved in his community, even going to Eastern France in the 1950s to help rebuild a war-torn town. He said that his inspiration for becoming an active member of his community and for his civil rights activism came from the encouragement from his family. “I grew up knowing that I was loved,” Barber said. “Being loved without conditions meant you could love other people without conditions.”

Barbara Cooper • Mar 7, 2021 at 12:49 AM

My late husband Fred Cooper was primarily instrumental in attaining equality of access to public services such as fire/rescue and municipal services in Bolton Mississippi. He should be given credit for this and all the other work he did in his life to selflessly advocate for economic fairness.

Barbara Cooper • Mar 7, 2021 at 12:37 AM

My husband Fred Cooper was very much an instrument in advocating for voting rights and access to essential services, especially the access to planning for fire and rescue services in Bolton, Mississippi. I wish credit was given to Fred , as his passion was for freedom, justice and equality for all. No exceptions. And he should be given credit here.