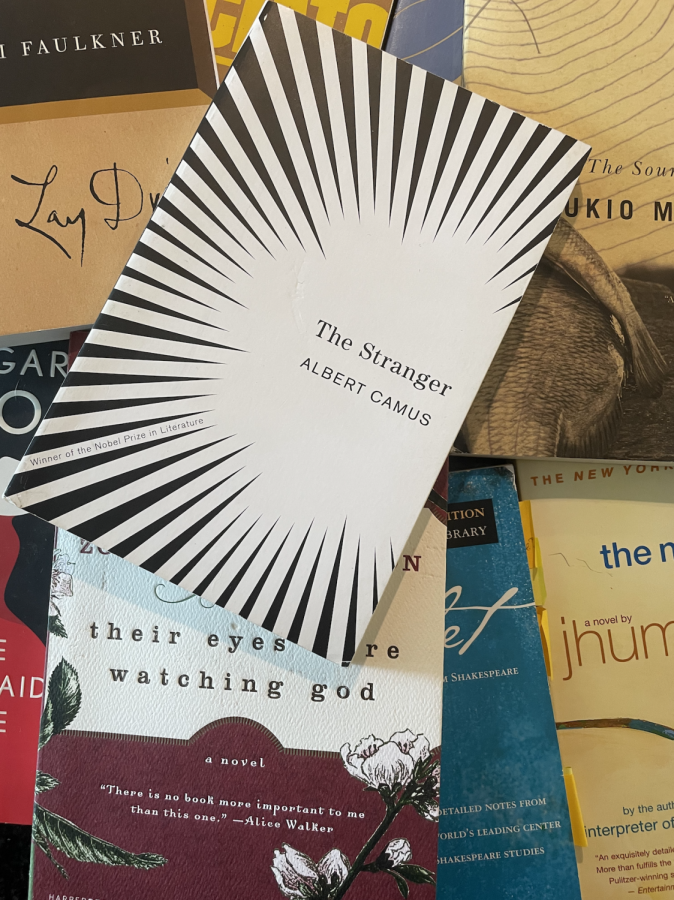

Wall-to-wall books

English department changes required texts, seeks to be more inclusive

Books read in the two year IB HL English class are stacked together. The teachers who instruct this course worked to include culturally diverse authors in the latest update to the county’s required book list.

BoThis year, the county’s English Language Arts (ELA) department is reevaluating the texts English classes will be required or allowed to read, and have some potential changes in mind. This process, which began 15 years ago and is redone every two years, was designed to prevent middle schools from teaching books that would later be covered in high school.

“To be honest, five to 10 years ago, we would review it and nothing would really change,” ELA Secondary Specialist Ms. Sarah Congable said. “We take off a few titles, maybe we’d add a few titles. And then in the last four years, we’ve had some pretty significant removals, mostly as our country’s become more woke, for lack of a better word.”

Ms. Congable described two examples of these changes — authors like Sherman Alexie and Matt de la Peña, who have traditionally been popular authors among English classes.

“They’ve had a lot of personal and professional information come out that made us as a district uncomfortable saying, ‘we should reserve those titles.’ We don’t really want them on the list. [Teachers] can still teach them, they’re still in the book rooms, you can read them. But do we want to say that every kid [should be] exposed to an author that maybe is in some questionable situations with women or with his or her cultural community? No.”

The high school English reserve book list includes two categories of books — core texts and variable texts. Core texts, which every student at the indicated grade level is expected to read, and variable texts, which teachers can choose from. “To Kill a Mockingbird” has been a core text for freshmen, and it tells the story of racism in a small, rural town. However, because it is told from the perspective of a young white girl, it has been debated in the English community.

“To Kill a Mockingbird is a big one, a lot of teachers want to see it gone,” Ms. Congable said. “Not because it’s not a great book, and it hasn’t done a lot for African Americans and for women in the past, but because of where we are now, it’s not maybe the best book to do it; it’s still a white person that’s writing it, it’s still a very limited white savior trope.”

In recent years, instead of teaching “To Kill a Mockingbird,” freshmen and Advanced Placement (AP) English teacher Mrs. Courtney Holcombe taught “All American Boys” instead. This novel, written by Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely, tells the story of two teenagers — one Black, the other white — who confront police brutality and racial justice.

“[All American Boys] is super relevant,” Mrs. Holcombe said. “[While reading it] we studied the Black Lives Matter [movement’s] 13 principles. We looked at what each one meant and why it would be that way. I don’t do that with ‘To Kill a Mockingbird.’ With ‘To Kill a Mockingbird,’ we talk about the history of the Scottsboro boys, all this really old stuff. And yeah, [we] can talk about how there’s still racism that exists, but [the example of the Scottsboro boys is] not as relevant.”

For some students, stories written by individuals personally affected by these issues may be more impactful.

“I understand the importance of reading the classics, I do, but who gets to define the classics?” senior Laura Jayne said. “I think expanding the authors that we represent, just kind of having a more diverse background is something I really appreciate. Like an author of the LGBTQ community, for example — I don’t think I’ve read a single book with author who identified as queer, and I feel like I would have really enjoyed that. And also, the same thing goes with race and ethnicity; having kids be engaged because they can see themselves in the book.”

Jayne is currently in the higher level International Baccalaureate (IB HL) English course, which is a two-year course over students’ junior and senior year. The IB curriculum is influenced by the preferences of the international IB office. Texts in this course include “The Remains of the Day,” by Kazuo Ishiguro, “Going After Cacciato” by Tim O’Brien and “Song of Solomon” by Toni Morrison.

“When we were reading ‘Song of Solomon,’ I think it brought up a lot of good points about how racism and systemic oppression weighs on like the Black community,” Jayne said. “I thought that was really important…a lot of themes from that book, they showed up over and over again in 2020 and over the summer, and now. And I enjoyed reading about that and getting a different perspective.”

Another factor that Jayne appreciates in her books is relevance — she enjoys books that discuss the themes and issues that impact students today. This is a factor Ms. Congable said has led the English curriculum to more Young Adult (YA) literature.

“I think the most important thing [about YA literature] is they’re writing with teenage protagonists,” Ms. Congable said. “For a teenager to see a teenage protagonist dealing with heavy hitting topics, or heavy hitting scenarios, validates kids who have gone through similar situations, and it is very eye-opening for other kids who might be more sheltered who should see that this is happening in the communities that they live in. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the most successful YA writers tend to be writers of color, and tend to be the writers who are telling stories that haven’t been told in the past.”

The text Mrs. Holcombe has replaced “To Kill a Mockingbird” with, “All American Boys,” is a YA novel. The concern about putting YA books on the official reserve book list, however, is that it may prevent middle school teachers from doing the same.

“I don’t want [some YA books to be on the high school curriculum] because of middle school,” Ms. Congable said. “Because there are kids in middle school who are voracious readers and voracious thinkers and are ready. And if you put ‘The Hate You Give’ on a 10th grade list, then what about a seventh grade teacher who has a classroom full of kids ready, that are already talking about those ideas and want to read a book about it?”

However, high school classes have other texts to give relevance to English class. Both AP Literature and IB HL Year Two read “The Handmaid’s Tale.” Mr. David Peters, the department chair for English and IB HL year two teacher, said the IB HL English teachers end the year with that text intentionally.

“In the past couple of years, we purposely ended the year with ‘The Handmaid’s Tale,” Mr. Peters said. “That’s always been a great book to sort of end the year with because I do think it leads to a lot of really interesting discussion. And, you know, with the state of a lot of things that are going on in the world and in the country, that novel has sort of taken on this new relevance that makes it a really good one to discuss.”

In the future, Mr. Peters said the course may include texts such as “Woman at Point Zero,” which is Egyptian, and “The Truth About Stories,” which is a collection of short stories from Indigenous culture.

With realism and relevance to today’s issues, though, comes mature content. For instance, in her ninth grade classes, Mrs. Holcombe teaches “Night,” a memoir by Elie Wiesel that recounts his experience in the Holocaust. Students are given the opportunity to opt out of reading the text, but Mrs. Holcombe said that has only occurred once in her fifteen years of teaching it.

“I think when we have discussions, one of the things that I think is important is to not pretend that ninth graders don’t know these things,” Mrs. Holcombe said. “Violence and trauma are everywhere.”

At the other end of the reading level spectrum, in upperclassman English classes, Mrs. Congable said there is an effort to show how enjoyable reading can be.

“I think the push at 12th grade is to say, this is sort of our last chance to build a reading life,” Congable said. “Let’s be honest, even your English teachers don’t pick up Shakespeare for fun. We don’t read Faulkner on the beach. We just don’t. We want you to always find books as a way to process the world around you and what’s happening, and find camaraderie and ways of thinking and find challenges in ways of thinking.”

The list — last reviewed in 2018 — is created after feedback from teachers and students is received. It balances all of these factors, plus AP and IB requirements and the appropriateness of each text for each grade level.

“To know that a kid from Wakefield reads the same as a kid who’s at Langston, and [it’s the same] at HB Woodlawn, that is what makes Arlington great,” Ms. Congable said. “So to think about what those books are, what those most powerful books are, that can move children forward, and to buy into those as a district. That’s been a work in progress for a long time, and it’s going to keep being a work in progress. Yeah, that’s pretty cool.”