APS second quarter data shows widening achievement gap

In the School Board’s meeting on March 11, data from the second quarter showed a large gap between the achievement of white, English-speaking students and students of color and English Language Learners (ELLs) during remote learning.

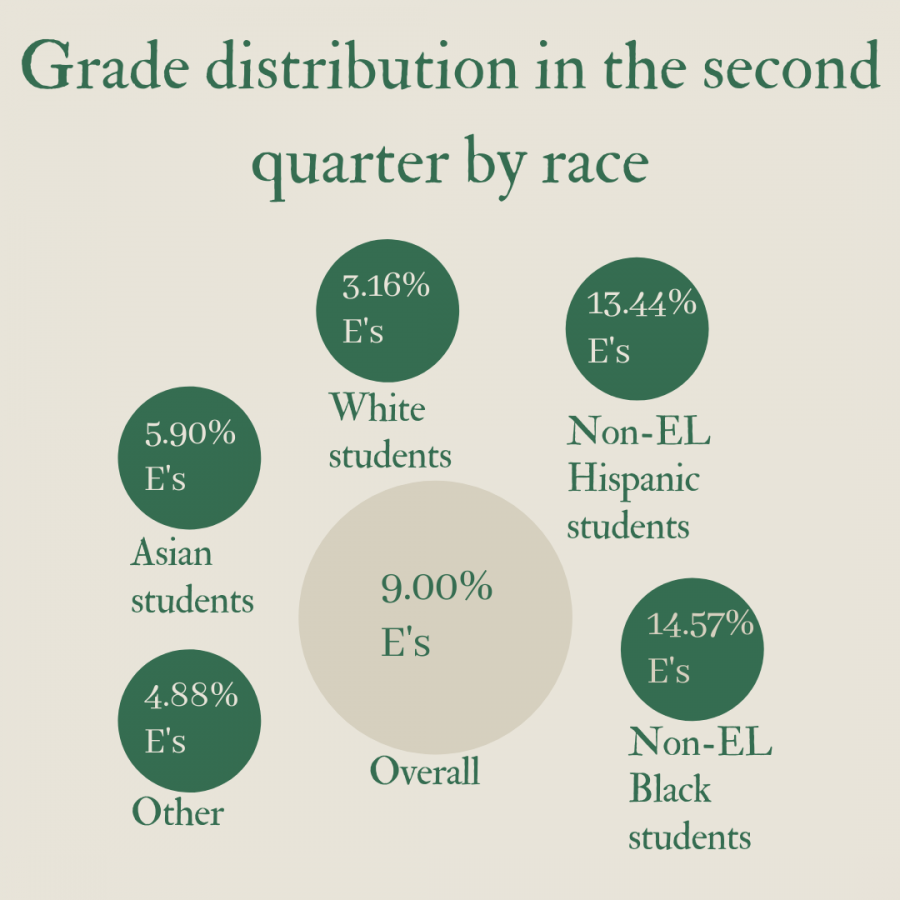

County data showed the proportion of E’s for white students was 3.16 percent, which was up a percentage point from previous years. These proportions were similar for Asian students. However, Hispanic students experienced a fail rate of 18.25 percent, as compared to a rate of 12.36 percent in the 2019-2020 school year. For Black students, the proportion of E’s jumped from 10.34 to 13.85 percent between last year and this year. Thus, though the percentage of E’s is higher for all students this year, this gap has disproportionately impacted Black and Hispanic students.

“Equity issues became visible now but have always been there,” Arlington Career Center (ACC) Equity Counselor Ms. Monica Lozano Caldera said. “The internet is a simple example. When COVID-19 hit us, we were looking for families to offer them free internet or low cost internet services. We know that [lack of internet access was] happening before COVID, but now it’s so visible that we need to address them directly.”

Internet access is one factor of many that contributes to the equity gap. In this case, the equity gap refers to the disparity of failing grades between different groups of students. Quarter two data showed that while the number of E’s increased this year, so did the number of A’s; this year, the divide between students who are failing and students who are succeeding in their classes has grown. At Washington-Liberty, many students are either the first in their family to attend college, economically disadvantaged or the children of immigrants. As a method to address these issues, Mr. James Sample’s position as Equity and Excellence counselor was established.

“In Arlington, in the past thirty years, we have tried to address [the equity gap] in a direct, strategic way,” Mr. Sample said. “My position came about almost thirty years ago to support students [in] passing the SOLs, getting more students into college and getting more students to get their degree.”

Mr. Sample recalled that his mother was surprised when he explained his job to her — she said if he really wanted to see an achievement gap, he should have seen the segregated schools she attended. As Mr. Sample explained, the effects of segregation and other historically racist precedents have impacted schools to this day.

“Brown vs. Board [of Education] happened fifty years ago,” Mr. Sample said. “There’s been systemic racism, Jim Crow, all those historical pieces. In the past fifty years, we’re dealing with major indicators. Indicators such as in Arlington, there’s an overrepresentation of black and brown students in special education. There’s an underrepresentation of those same students in gifted education.”

Furthermore, housing and socioeconomic status are factors that cause greater divides. Specifically during the pandemic, certain zip codes have been disproportionately hit with COVID-19 cases — 22204, for instance, has more than twice the number of cases per 100,000 people that 22213 has. This divide could be due to a number of factors, including the location of nursing homes and apartments, as well as the population density of each respective zip code. Students who live in apartment buildings struggle with economic and health risks. Even going outside can be difficult, as anyone across the hall or in the elevator could be a risk for the family. That worry can be compounded if a parent is working.

“Some kids I’ve talked to, they say that their parents are going to work and [they’re] concerned [they] could get sick,” Mr. Sample said. “Many of our kids and parents are working on the front lines — are working in grocery stores, are working in restaurants, are working in hospitals or driving school buses — so many of these kids have been thinking since March, ‘What happens if my mother or father gets sick? What if somebody in my building gets sick?’”

The ELL program is broken down into different levels. Levels One and Two are for students who have just entered the country — these students receive the most intensive English lessons and have been especially negatively impacted by online schooling. Next, Levels Three and Four are halfway out of the program, and Levels Five and Six are in “regular,” or completely English classes, with accommodations. For English Language Learners, fail rates for the lower levels (Levels 1 through 4) of EL education have jumped from 16.12 percent to 25.72 percent. Ms. Lozano Caldera works with students in the EL (English Learners) Institute, a program in the Arlington Career Center dedicated to English Language Learners.

“My students don’t have extra time after school,” Ms. Lozano Caldera said. “My second language learners, or third language learners, for them the moment that they are in class is the only moment that I get from them. When they leave, they are in survival mode; they have to go to work.”

Due to the economic recession brought on by the pandemic, unemployment has increased dramatically, reaching a high of 14.8 percent in April of 2020. Racial and ethnic minorities have faced the worst unemployment numbers (16.9 percent for Black workers and 18.9 for Hispanic workers.)

“I think, for sure, the basic needs of getting, you know, shelter, food, that has definitely increased significantly during the pandemic,” Washington-Liberty social worker Ms. Heidi Baptista said. “I’ve been at W-L for maybe 13 years, so I can see that difference. And I think I have to say it’s across the board and throughout Arlington.”

Senior Scarleth Barrera attends the EL Institute. Barrera works at a restaurant in Clarendon and gets home from work around 11 to 11:30 at night. Only then can she start her homework, which takes her one to two hours.

“Every day after school I have to work,” Barrera said. “It is a little bit difficult, because you’re doing [school and work] at the same time, so for some of us, it’s a bit complicated. But, we have to work after school because we have to pay for things like rent, food, and things like that.”

Despite the challenges caused by the pandemic, Barrera said she worked more before the pandemic, sometimes closing at midnight. Many of Barrera’s friends also work after school, as well as her mother. Barrera lives alone with her mom while her siblings live in Honduras. Her mother works for longer hours and often returns home after her.

“Sometimes it’s a little hard [when she’s not around], but when you are doing something frequently it’s normal for you,” Barrera said.

When school was in-person, Ms. Lozano Caldera said the Career Center’s Career and Technical Education (CTE) classes, which focus on practical skills such as car repair and graphic design, bridge the gap between ELs and those fluent in English.

“The Career and Technical Education classes really help us to create these spaces where the students will feel safe, doing things together, and with different languages and learning how to talk to one another to have the job done,” Ms. Lozano Caldera said. “[For example,] we have students who know how to repair a car. They don’t know the name of the parts in English, but they have done it in their country and they can share and work with others.”

However, now that school is happening remotely, ELs have been especially impacted by the new form of learning.

“Online teaching does not [compare to] what you did in the classroom before,” Ms. Lozano Caldera said. “You have to be able to engage and support students with a better vocabulary page, maybe with subtitles, maybe a lot of links and resources where they can practice their English in particular.”

Arlington Public Schools (APS) began its high school hybrid transition to Phase 2 and 3 on March 9 and 16. By the week of March 16, any high schooler who prefers hybrid learning began to learn in-person. Washington-Liberty principal Mr. Tony Hall hopes students will learn more effectively.

“I think that statistically, given what we know about students being able to work with individuals one on one, with the effect of students being in school and feeling a higher sense of self efficacy and connectedness and self esteem….it is reasonable to assume that the failure rate will decrease, because of the fact that more students are in a situation that is familiar; being in a brick and mortar school is a lot more familiar,” Mr. Hall said.

Mr. Sample and Ms. Lozano Caldera both commended their respective programs for establishing teams of psychologists, counselors, administrators and bilingual liaisons to reach students who are in need of resources or help.

“We also have the Hispanic Parent Teacher Association, and they’re very active, and they’re led by very, very strong leaders who also are helpful in the community,” Ms. Baptista said. “We try to get information out in English and in Spanish, and [in] other languages, because you know, even though our Spanish speaking families are a lot, we still have a lot of families from other different countries. So again, trying to connect with families in any way that we can, in any language that we can.”

Ms. Baptista said the decision to include General’s Period (GP) on Mondays has been especially helpful. This year, each staff member has been given a GP in an attempt to give students an easier one-on-one connection with an adult in the building.

“One thing that I’m very grateful for is this GP period that we’re having,” Ms. Baptista said. “I thought that this was a great way for more of us to be available to students in a smaller setting. I really think that has been very, very key for a lot of students. Not all students, but definitely I think a more targeted approach.”

Mr. Hall said he believes in “doing better things” rather than “doing things better.” For instance, assessments could be evaluated on content comprehension through discussion rather than a formal test. A student could demonstrate a math problem rather than complete a traditional assessment. He said that allowing students to prove their comprehension in unorthodox ways could help all students, and especially students of color and ELs.

“It keeps you up at night, truly,” Mr. Hall said. “When you know that kids aren’t doing well, for whatever the reason is, whether it’s just strictly academic or there’s something going on in their lives, beyond their control as young people, it truly does. I have a son. I am a son. And so, I think about it from all those different perspectives. And so, as long as I’m the principal of W-L, I’m going to continue to sort of be involved from 30,000 feet, and then from on the ground.”

Even after the pandemic, Mr. Hall said the issues the school is tackling now will continue to be addressed. For instance, reevaluating grading and the merit of a zero in the gradebook, as well as tackling long-range questions such as housing and mental health.

“There are certainly some issues that I think have been magnified by the pandemic, [but] there’s no doubt that the achievement gap existed, before the pandemic,” Mr. Hall said. “And I think it’s incumbent upon us as educators to continue to try to do better things, because the pandemic has exposed some of the things that, quite frankly, I think we need to work on. The one thing you’ll find out about me as principal is I don’t run away from those conversations. They’re tough conversations to have, but you have to have them.”