Students for racial equity club and its pioneers

The newly emerged Students for Racial Equity Club (SRE) and its leadership team

SRE’s leaders

Hundreds of students take advanced classes, many even go on to graduate with Advanced Diplomas. However, an uncomfortable experience persists. Students of color step foot into their advanced courses, yet notice that there is barely anyone that looks like them, and that they are one of the only students of color in the class. This is an experience that several students of color continue to experience.

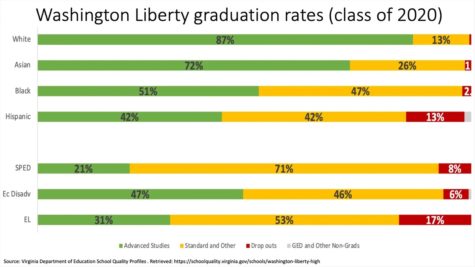

As of 2020, 87% of white students graduated W-L with an advanced studies diploma, while 72% of Asian students, 51% of Black students, and 42% of Hispanic students. Despite the school having an incredibly high graduation rate, the rates of students of color taking advanced courses compared to white students show major discrepancies.

However, the Students for Racial Equity club (SRE) is determined to start conversations about the issues that students of color face in order to create a school system that promotes equity for all students. The SRE club is not exclusive to the school but is a community-based club that has members from other APS schools including Wakefield.

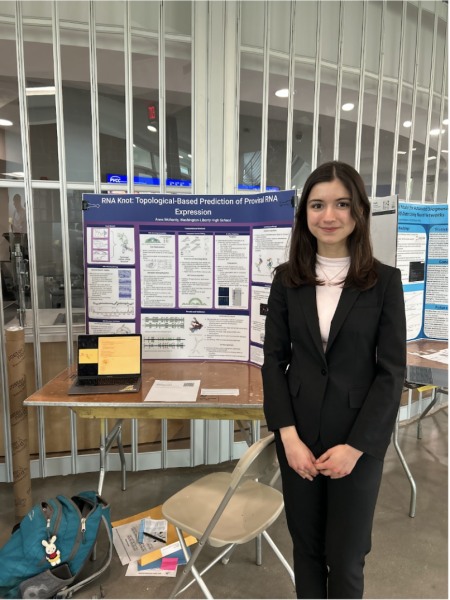

SRE was created in June of 2020 and was founded by two seniors at the school: Kimiko Reed and Amina Luvsanchultem.

“I am the president and founder of Students for Racial Equity, and my role in the club is not only managing the leadership team, which consists of three vice presidents, and two presidents, me and Amina,” said Reed. “It also means organizing club projects.”

Reed manages the outreach based aspect of the club: finding mentors, sponsors, and building relationships with organizations such as the NAACP. Meanwhile, Luvsanchultem handles the interpersonal part of the club, which is the connection between students and teachers in interviews or professional development sessions.

The idea of SRE had been in the back of their minds for a while. Reed and Luvsanchultem arrived at the school when the school’s racial dilemmas were very evident, specifically when the debate of the name change from Lee to Liberty was at an all-time high.

“Amina and I had known each other since freshman year when we were in the same AP World History class,” Reed said. “From the start, we were the only two kids of color in the classroom.”

Reed, who is half Black and Japanese, felt that both of her cultures were being misrepresented in the course. Luvsanchultem, who is a first-generation Mongolian student, felt the same way. These mutual feelings sparked a friendship between Reed and Luvsanchultem.

However, the events of the summer of 2020 led Reed and Luvsanchultem to pursue SRE.

“Me and Kimmy during quarantine, especially after the murder of George Floyd, and a lot of the events that were happening, needed to talk about things,” said Luvsanchultem. “We had really good conversations that I’ve never really had before about racism and inequities in the school, and inequity in general. That’s a kind of a discussion I haven’t really had before and after talking with her, I asked what if we did something about it, and we came up with a plan to create SRE.”

SRE’s leadership consists of five people total, including three vice presidents, all of which have different roles.

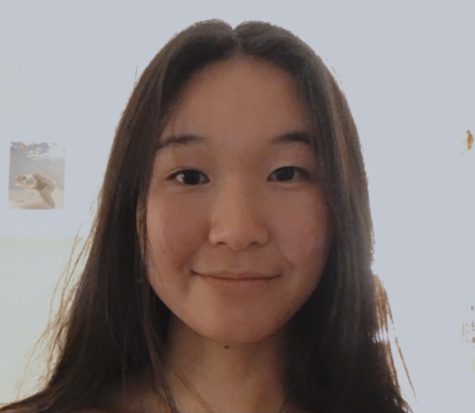

“My job is basically to help individuals create blog posts to post on the SRE website, so I’ll help them (members) brainstorm ideas for the blog post, and help them along the way,” said Sarah Ahmad.

Ahmad is a sophomore at the school and SRE’s vice president of content development.

“I joined SRE about a year ago, around when it first got started. I then applied to be the vice-president of the club and I got the position. I really want to advocate for students of color within APS and within our community,” said Lara Mohamed.

Mohamed is a junior at the school and SRE’s vice president of production. She summarizes the stories of students who participated in empathy interviews, in order to start discussions regarding the subjects with teachers. She is also a part of several other clubs, and vice president of both the Black Lives Matter Club and Muslim Student Association.

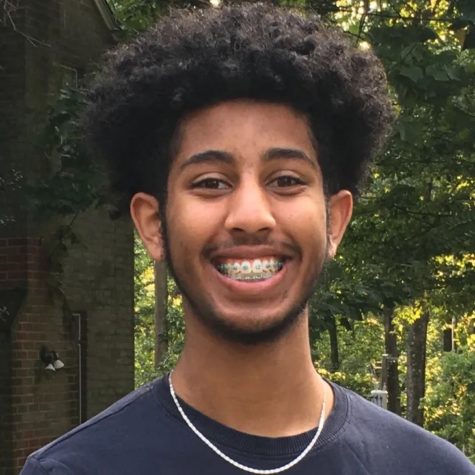

“I handle the Instagram, the Twitter that we have, and we’re planning on making a snapshot and maybe expanding our other social media to reach more people, said Leule Ashenafi.

Ashenafi is a senior at Wakefield High School and is vice president of communications and outreach. He was born in London, England and immigrated to the United States in 2017.

The members of SRE all have different reasons for joining the club, however, they have all faced several experiences that inspired them to join the club.

For example, a key experience in Ashenafi’s life is having been placed in English Learner (EL) classes when he moved to Arlington, despite Ashenafi having been fluent in English as he moved from the United Kingdom.

“We provided my transcripts to my previous school (middle school), my ability to speak and perform English properly, like reading and writing,” said Ashenafi.

“I think that the main issue was that I was bilingual. I think that the main issue was that I was bilingual because I said that I spoke Ahmaric fluently and it may have been stated that I spoke Ahmaric first too,” said Ashenafi. “It was disappointing more than anything. I wasn’t even angry but I was disappointed,” said Ashenafi.

Meanwhile, Luvsanchultem’s experience being a first generation Mongolian and dealing with the dilemma of whether or not to assimilate, or embrace her culture, led to her founding SRE.

“There’s an assimilation culture in our school and society in general,” Luvsanchultem said. “I was kind of conflicted about that, whether I should become fully American, or whether I should just stick to being Mongolian instead of being that kind of in-between.”

Assimilation is the process of fitting into the predominant culture or belief. In this case, it involves attempting to fit into American culture. Assimilation is something that many students of color have experienced, especially in situations like Luvsanchultem’s where she is typically the only Mongolian student in her class. Therefore, there is an urge to shy away and feel ashamed of one’s own culture in order to conform to American culture.

However, after creating and joining SRE, all of these students have been determined to initiate conversations between teachers and students regarding equity. To do this, they tell the stories of real students, which they acquire from empathy interviews.

“We interview students through empathy interviews, and then from those interviews, we analyze them for common threads and themes, finding the pattern across all these stories to say, “Hey this is a trend that is happening to so many kids that this is now a systemic issue embedded in your school,” said Reed.

Additionally, Ashenafi was introduced to SRE through the empathy interviews as he himself was interviewed by Reed before joining the club.

A key aspect of SRE’s empathy interviews is the aspect of anonymity which they guarantee each student.

“We anonymise the names of the students and never reveal whose specific story we’re telling, which allows more students to express their experiences without feeling like they are going to be in a complicated situation,” said Mohamed.

The anonymity keeps the students from being in positions that could potentially cause tension between teachers and students, especially if the student is identified.

In order to identify trends of systemic racism within the school system, SRE thoroughly analyzes the interview. Two trends have been identified throughout the empathy interviews: Issues within English and Social Studies classes, and students of color not being encouraged to take advanced courses.

“It’s usually the English and History classes that tend to be the issue,” said Luvsanchultem “[for example], saying the n-word because a book said it or something. Those issues need to be addressed, and I don’t think that has been addressed enough because the administration doesn’t know what happens in classrooms.”

Luvsanchultem has had her own experiences with history classes being extremely Euro-centric, especially as a Mongolian student.

“The first thing that pops into people’s mind is like Ghengis Khan right? The conqueror of half the world and you just see him as an evil person,” Luvsanchultem said. “He definitely did bad things, but seeing him from the Mongolian side is a way to incorporate different perspectives.”

In class, one may not think about these other perspectives that exist, especially regarding history such as that of Mongolian culture, which has a very specific and violent reputation in American world history classes.

“It’s interesting because all my life, my parents were like, ‘Oh, [Ghengis Khan is] a hero.’ He is a hero for Mongolians because he made the Mongolian culture known to others,” said Luvsanchultem.

In one of Luvsanchultem’s old history classes, they had to debate whether or not Ghenghis Khan was good or evil. She was placed in the evil group, and said that she felt as if she changed her views a bit. However she felt that her peers hadn’t, due to them not having learned about Mongolians’ point of view about the subject.

In English courses, several students of color have dealt with racial slurs being said in class, solely due to the fact that the slur is present in the book, despite the students’ discomfort.

Next, the issue of students of color being discouraged from taking advanced courses, or simply being told that they cannot take these courses despite being fully prepared.

“When I was in eighth grade, I was taking rural geography and I wanted to take AP World History in ninth grade, but my teacher was reluctant to place me in an AP class,” said Ahmad.

“He (teacher) would tell me ‘Oh, that class is really hard and you get a lot of homework, do you think you’ll be able to handle that?’ Whereas my white friends got placed in that class, so I felt like there was this bias, but I mean, I ended up getting placed in that class and I was able to handle it in ninth grade,” said Ahmad.

Reed herself, who has been an all-A student since middle school, has experienced similar issues.

“I’ve been a straight-A student,” said Reed. “Regardless of that, I have to meet with my counselor, and I have to bring in my parents and bring in my full repertoire of all the work that I’ve done to justify me taking an advanced course.”

She soon realized, after discussing said experiences with her white peers, that they did not share the same experiences.

“The extra layer of justification and making my parents take time off of work, just so that they can vouch for me is something that I know from asking my white peers do not have to experience,” said Reed.

Reed was asked by superiors whether or not she was sure if she wanted to take advanced classes. Reed was told that she could not take these specific classes.

“Why do you not think I could be in this class,” said Reed. “Because you may be right, and if you are right, I would like to know the reasons so that at least I have the opportunity to better myself and work on that. If not this class, then what?”

Reed’s parents were able to take time off work to vouch for her, but what about the students whose parents cannot? What if the parents are able to take time off, but don’t speak English? What happens next? These are concerns that she is determined to solve through the SRE. They hope to encourage students of color to become self-advocates for their needs and rights.

On the half days on Wednesdays, SRE had an opportunity to do somethingLuvsanchultem and Reed had dreamed of: Conducting professional sessions.

Teachers from the school were required to take a select few school-based professional development courses, but were then given a choice ,and SRE was on that list.

“It was pretty incredible that after so many years of being unheard to know that there were teachers who were like, ‘I haven’t had the opportunity yet, but I really want to hear you,’ and that feeling was pretty awesome and empowering in and of itself,” said Reed.

In the professional development sessions, SRE members conducted several activities and discussions with the teachers.

“We had two main games; [it] was kind of broken up into two segments. The first segment was we had introductions about ourselves about what SRE is, what we aim to achieve,” said Ashenafi.

“The second portion of our workshop we had a discussion, where we had envelopes and we had maybe 30 to 40 teachers and each teacher got an envelope, and there were four envelopes that had student stories inside of them, which were pulled directly from our empathy interviews because nothing was hypothetical, everything was real,” said Ashenafi.

Afterwards, those four teachers that stood out because of their envelopes had to read aloud to everyone, the story in the envelope.

“We were trying to explain to teachers how it would feel to be a minority in an AP classroom, where a lot of the students aren’t of color. That’s why we had a majority of the envelopes be empty, so we could teach what it’s like to the only one,” said Ashenafi.

Reed also mentioned having conducted an activity where statistics and math was fully involved to explain to teachers the discrepancies in the amount of white students compared to students of color, and how that is viewed from a teacher’s perspective rather than that of a student.

With the teachers, the members also broke into discussion groups where racism and equity were discussed and the efforts that teachers were putting to ensure an equitable and inclusive classroom.

“Through these conversations, I was able to see how most teachers really try to instill equity in their classrooms, and that was inspiring for me and interesting,” said Luvsanchultem. “Hearing about all of these experiences from students, all these bad experiences, I guess I had lost hope in some way. But speaking with these teachers, I was able to see that there is hope.”

This year is Reed, Luvsanchultem, and Ashenafi’s last year in SRE due to their status as seniors, however, all have big plans for SRE’s future.

“We plan on making it a nonprofit organization in the very near future, and making SRE bigger. We were planning on having committees like focusing on education equity, housing equity, wage, food instability,” said Luvsanchultem. “SRE will become, not just students for racial equity, but a broader range and possibly taking SRE to our colleges, and we’re definitely not going to stop here.”

Despite SRE having been founded recently the bonds and connections formed between the members are evident.

Mohamed emphasized an important distinction that has to be made in order for true understanding and change to occur.

“Inclusivity is different than diversity. It’s easy to be diverse because that means bringing in many different students of multiple backgrounds. It’s harder to make those students feel included. APS is diverse, but needs to work on inclusivity. We need to include more students in IB/AP classes, include more parents of students of color,” said Mohamed.

Ahmad wants to encourage students to stand up to racial inequalities, and have their stories, and other students of color’s stories be heard. Ahmad had the following message for those interested in joining SRE:

“You can always participate in these seminars with other teachers to get your point across and to talk to them about these inequities,” Ahmad said. “Especially if you want to create a change because that’s how you can create change within your school system, by talking to teachers about these systematic barriers and trying to advocate for fellow students of color and empower them.”

Club founder and co-president Luvsanchultem had a final message for students of color:

“If you’re a student of color, and you’re kind of experiencing confusion, or this feeling of being alone or feeling isolated, just know that you should feel free to express your own culture and express yourself as you are,” Luvsancultem said. “I have found that to be really important throughout my journey, and I just wanted to emphasize that for students of color who are experiencing the same thing that I was. Don’t feel the need to become Americanized or the need to forget your culture to fit in, and I think that’s a big thing in high school, and I just wanted to emphasize that for students of color.”