Coronavirus classroom: from coast to coast

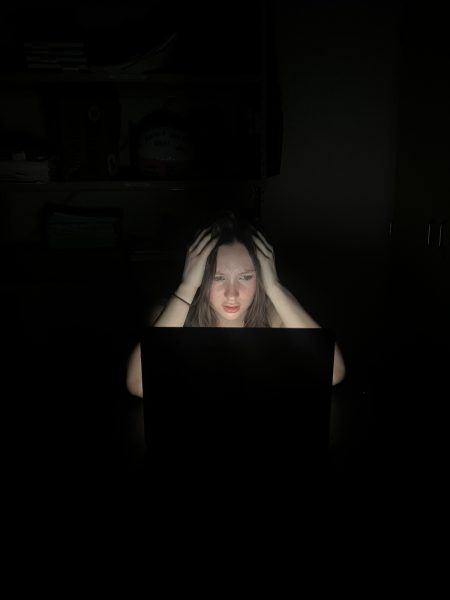

Heavy eyelids drooping, mind weary, I left the Zoom call at last.

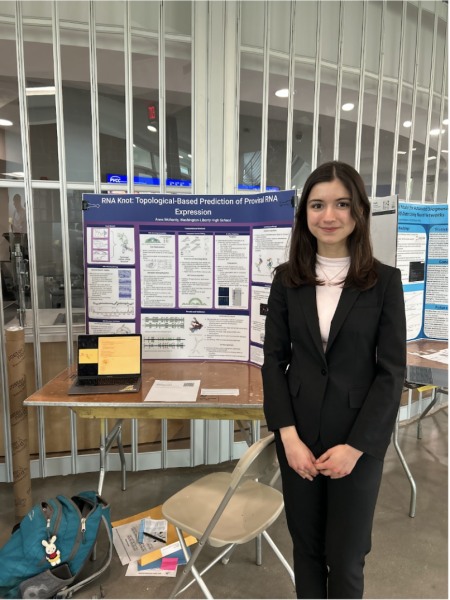

My junior year at Palos Verdes High School (PVHS) in California had just begun. This school year was going to be unlike any other — and not just because of online classes.

During my second week of school, my parents told me that due to the unpredictability of COVID-19, we were moving back to where I grew up — Arlington, Virginia. Only a few days before school in Virginia was set to start, I hastily picked my classes. Before I knew it, I was starting online school all over again — this time at Washington-Liberty High School, on the complete opposite side of the country.

Having attended two different schools, in different school districts and states, what strikes me the most is that both schools had the entire summer to devise what they thought was the best plan for virtually starting the 2020-2021 school year, but one district clearly met the needs of its students better — Arlington Public Schools (APS).

The main reason why school in APS has been better is the overall structure of the online classes.

Camera policies vary across school districts

In California, my camera was required to be on at all times, contrary to the camera-optional approach at W-L. Yes, having cameras on helps ensure student participation, and teachers can better gauge understanding, but the cons far outweigh the pros.

At PVHS, you would get in trouble if you turned your camera off — your teacher would call you out in front of the entire class, and you could lose participation points. An important factor to consider is that my classes were 100 minutes long — that’s 100 straight minutes of purely synchronous time. Being on camera for so long was draining, making it difficult to concentrate.

The many strange rules about what you could and couldn’t do on camera complicated online learning. You couldn’t go to the bathroom unless you announced it in front of the entire class, and you weren’t allowed to eat on camera, despite having gone hours without food. Nor were you allowed to be in bed.

The most questionable rule was this: teachers constantly reminded us that failure to be seated physically at a desk would also result in a loss of participation points. My classmates in California were told by the teacher (for all on the Zoom call to hear) that they had lost participation points for sitting up in bed or even sitting on a sofa. Because these points can often be crucial to having a good grade, this rule is not only unfair, it’s completely unreasonable. Not everyone has a desk, or, like me, you could be traveling or have your parents working from home, so the only quiet working space to focus is your room.

The on-camera rule resulted in greater stress and less focus on actual education.

At W-L, I’ve had a much more pleasant experience — I put my camera on to participate and ask questions, but I can turn it off to work in peace. This has also enabled me to be more engaged in learning. For example, I had to be away from home for several doctor’s appointments due to a wrist injury, but I was able to participate in class discussions even though I wasn’t at a desk — something I would have lost points for in California.

School districts mandate differing class time requirements

The biggest benefit of attending W-L is the balance between synchronous and asynchronous time, which leads to enhanced learning, productivity and a better state of mind.

In California, my school day was entirely synchronous, with three 100-minute classes and one 50-minute class per day. There were no scheduled breaks, with most of my teachers choosing to use all 100 minutes of instruction time. Some teachers allowed the class to leave 10 minutes early, have 5-minute stretch breaks, or occasionally go off-camera for work, but this was rare and inconsistent. At the end of the day, the synchronous learning time was just too much to expect students to stay engaged.

On the other hand, teachers at W-L have stressed the importance of not being on the computer or looking at screens for too long. They even allow us to have short stretch breaks and respect the scheduled asynchronous time. These may seem like small things, but they make a big difference.

PVHS’s lack of asynchronous time was accompanied by the lack of opportunity to complete homework throughout the day, meaning there was significantly more work to do after class and on weekends. Focusing on lengthy, online classes all day was exhausting and added an extra degree of difficulty to completing homework.

The asynchronous time at W-L is so valuable, allowing students to start working right after the class lesson, and to even rejoin the call to ask the teacher questions. Most importantly, the W-L approach allows students to do homework throughout the day rather than facing a mountain of homework at the end of the school day.

The lack of asynchronous scheduling on the part of Palos Verdes Peninsula Unified School District was an abject failure — promoting an unhealthy amount of screen time and a poor balance between school and mental well-being. APS’s thoughtful inclusion of scheduled asynchronous time results in a much more balanced and productive educational experience.

Scheduling approaches result in unequal outcomes

Another factor that makes W-L’s schedule so much better is the no class Mondays. On the other hand, PVHS chose to make Wednesdays all-class days, cramming instruction for all six class periods into one day — which was a terrible decision.

Having all six classes on Wednesdays resulted in an unmanageable workload, defeating the purpose of block scheduling and inducing significantly more stress.

W-L’s approach of only having a 30-minute General’s Period (GP) class on Mondays provides a much-needed catch-up day. As a result, students aren’t nearly as stressed and don’t have to spend their whole weekend doing homework.

Technology can simplify or complicate learning

PVHS’s scheduling downfalls were compounded by issues with teaching platforms. Teachers at W-L use Canvas and Microsoft Teams. At PVHS, teachers were supposed to exclusively use Google Classroom, Google Meet and Zoom, but every single one of my teachers had their own website that students were required to check for assignments. Canvas is much easier to navigate because all homework is well organized in one place.

Not only were classes at PVHS split between Google Meet and Zoom, not all teachers were clear about which one to use and login codes often changed: tough luck if you clicked into the wrong platform or link. It’s so much simpler to open Microsoft Teams and just click “join” for the class you want to attend.

Overall, the lack of cohesiveness among the platforms made it really hard for students to actually learn, attend class and do assignments. Yes, I understand that it’s difficult for teachers to adjust to using new platforms such as Google Classroom or Canvas, but consistency is essential to optimizing the student experience.

One thing about school in Virginia that has been worse than in California is technological issues, such as getting kicked off calls. Admittedly, my difficulty accessing assignments on Canvas is mostly attributable to being a last-minute transfer student to W-L, but issues have been widespread.

Consistency and adaptability are key to a successful COVID-19 school year

I have to consider that maybe if I had stayed at PVHS for more than the first two weeks of this school year, things might have gotten better. However, the fundamental issues behind my dislike of PVHS’s online class structure for 2020-2021 were things that couldn’t be changed easily and most likely wouldn’t change — the cameras-on policy, fully synchronous schedule, Wednesday all-class day and teachers using different platforms.

COVID-19 presents challenges, expected and unexpected. There’s no blueprint for how schools across the country should adapt to our new (and hopefully short lived) normal. But one thing is clear — having a framework in place that is consistent yet adaptable and understands student limitations makes the difference between an unhealthy learning experience and a successful one.