Loss of housing in the Arlington community

Crates filled to the brim with oranges surround senior Lea Karush as she begins her volunteer shift at the Arlington Food Assistance Center (AFAC). Karush has been an AFAC volunteer since before she can remember, but the support of other volunteers like her is more important than ever due to the new issue the world is facing: people losing their housing due to the pandemic.

According to Arlington Public Schools (APS) Homelessness and Foster Care Liaison, Barbara Fisher, however, this loss of housing is not a new issue in the Arlington community.

“In 2016, we had around 235 students identified as homeless,” Fisher said. “I say identified, to be distinct from everyone who lost their housing, because I’m not confident that we found everyone. Then for the next three years or so, the number was in the same range of 200-230.”

The numbers in the past year have also dwindled, which may come as a surprise to some.

“Last year, everything shut down in March, so we stopped at around 180,” Fisher said. “We normally would have identified more during that last quarter of school, but people were virtual and if they had lost their housing or had to move they didn’t necessarily tell us, because school was not very easy-access back then. This year, we’re now up to 126.”

This is an occurrence which, according to Fisher, has been happening nationwide. There are a variety of reasons for this, one being a surplus of rent relief, where local governments help citizens pay their own rent.

“Some landlords currently aren’t allowed to evict their tenants even if they aren’t paying rent because of the current circumstances, and the county helps with this, but it can’t go on forever,” Fisher said. “Another reason is that many students are still choosing to do full time distance learning, and as long as they have good internet access, under McKinney Vento, they can live in areas much farther away and still attend an Arlington Public School for the year, as long as they give back their device.”

While a well-known and important term to social workers like Fisher, the words ‘McKinney Vento’ likely remain unknown to many. The McKinney Vento Homeless Assistance Act was passed by Congress in 1987 due to research that showed that students who lost their housing were less likely to graduate high school or succeed academically, usually due to missed school.

“Kids often miss school for reasons that they can’t afford,” Fisher said. “For instance, maybe their laptop charger was lost when they had to suddenly move, or they don’t have reliable internet where they’re now living. There could also be other things going on, that if they don’t tell the school about, could count for unexcused absences, which could possibly make them look like they’re being bad or truant.”

According to USA Today and a study by Economic Roundtable, homelessness will continue to increase as a result of the pandemic in future years.

“Over the next four years, fallout from the pandemic is expected to cause chronic homelessness to climb 49% nationwide,” USA Today said.

This may mean that Fisher’s job in the future could involve helping a greater number of students than she does currently.

“My job as the homelessness and foster care liaison is to help connect students who have lost their housing and their families to services in the school division and under McKinney Vento that will help them stay stable in school,” Fisher said. “If we can keep their school life stable, then they can keep the same teachers and their same group of friends and not fall behind academically. If they’ve missed two weeks of school, if they had to move, or for whatever reason, people will start to ask questions, and many tests and assignments can be missed. As a liaison I try to make sure that the school part of their life can remain stable.”

According to Fisher, McKinney Vento was designed to eliminate some of the barriers that children face going to school if they lose their housing, as well as to provide them with extra help and opportunities.

“McKinney Vento guarantees continuous schooling for students, even if they lose their housing,” Fisher said. “It also guarantees immediate enrollment for a student if they switch the school that they are attending, without documentation… they get more time before they have to provide that information.”

The legislation also gives students who lose their housing the right to remain at their school of origin, even if they no longer live in the boundaries of the school.

“For instance, if you were a Washington-Liberty student, and moved to a Yorktown area, you still would be able to attend Washington-Liberty, even though Yorktown would be your school of residence,” Fisher said. “This also applies if someone moved to somewhere farther, like Fredericksburg. However, that can be a major burden. What we would do then is hold a best interest determination meeting, which I facilitate, and it helps to determine if it’s better for the student to attend their school of origin, or their school of residence, where they’re sleeping.”

McKinney Vento also made it so that a federal program provides each state with a budget to follow the rules it established, which involve each school division having a homeless liaison in place, as well as social workers at each school.

“Project Hope is the name of the program that ensures compliance with McKinney Vento, and it operates out of the College of William and Mary in Virginia because they are providing the logistics, the office space and so forth, and it’s where the state coordinator has her office,” Fisher said. “She is in charge of making sure that every school division in Virginia has a homeless liaison in place. Arlington is much smaller, so we had fewer students identified, but in Fairfax almost 3,000 were identified two years ago. Due to its size, Fairfax has a much larger staff.”

McKinney Vento defines homelessness as a number of things, one being staying in an emergency shelter, which Arlington has three of. This includes a shelter in an undisclosed location for people fleeing domestic violence, apartments, rooms and sometimes motels.

“Anyone in transitional housing also qualifies, which is when people move from a homeless shelter to an apartment building and they initially get help with paying rent,” Fisher said. “Over time, they try to have the family support themselves without that extra help.”

Usually found in more rural settings, campgrounds count as well, as does staying in public parks, buildings, hotels and motels.

“We’ve had students here in Arlington that have slept in the office building where someone that they know works, which is generally not good,” Fisher said. “Occasionally, we will also have families with people that are sleeping in their cars. It’s really challenging to go to school when you go to sleep in a car. We try to get them into a shelter as quickly as possible, but that’s not always easy, because they could have a family pet, or they could be afraid of going to a shelter.”

People who are missing a bed, kitchen, bathroom, or basic safety also qualify for McKinney Vento. Another category, known as doubled up, is one that Fisher said is one of the most common.

“Doubled up is where someone stays with a friend or family member or someone like that, but they likely aren’t paying rent and don’t have a lease, so they can be kicked out at any time,” Fisher said. “Doubled up is a pretty big category in Arlington, especially for older high school students. We don’t identify all of them, because oftentimes they might not be willing to share that information. Roughly, I think half of the students who lose their housing are in shelters, and the other half are doubled up.”

According to Fisher, Arlington’s specific program is known as Project Extra Step. It provides free meals, backpacks and tutoring to students. It also includes a grant that provides transportation when students can’t walk or ride a school bus, through smartrip cards or taxis.

“Project Extra Step allows us to ask for favors from teachers, like to excuse missed assignments, or to allow a test to be taken later, or try to discourage unnecessary discipline that ordinary students would get,” Fisher said. “These students need a little extra support, which is why we call it Project Extra Step.”

During the pandemic, the program has also provided more than what they have in previous years, including discounted Comcast home WiFi or hotspots for students without working internet.

“Now that students have begun coming back to school, the division has started providing them with masks,” Fisher said. “Along with that, laptop desks and headphones with microphones have also been distributed.”

Outside of an APS service that provides students with free eye exams and eyeglasses if they need it, somewhat free health care options are available in the county to students and families without housing.

“There are two services in Arlington that supply pretty much free health care, one being the Public Health Department, where you can get a lot of screenings and immunizations and some basic needs met,” Fisher said. “There’s also the Arlington Pediatric Center, which is over on Carlin Springs Road, and they all take families with no insurance. The Arlington Free Clinic is another one, but they have a waitlist.”

Once a student is identified as being without housing, Fisher and school social workers also try to connect them with community services. One example is the rent and housing assistance line from the Arlington County Department of Human Services: 703-228-1300.

“Along with rent assistance, there’s the Arlington Food Assistance Center (AFAC), and a place called Clothesline which provides new clothing to families if they’re referred to them by school social workers,” Fisher said. “We link them to all of these services, and also to the mental health teams that the school provides, and they can do emergency assessments, crisis information and counseling with kids when they need it.”

In the county, Fisher has seen many examples of poverty. This includes large areas where people housed in substandard places of living, like cellars of houses, as well as two bedroom apartments with two to three families in them.

“Oftentimes, bad things happen to good people,” Fisher said. “They can lose their job and get stressed, or become ill. If they become ill, then they could lose their job and income because they can’t go to work, and then they could become depressed. This is definitely not the case for all homeless people at all, but then they could turn to substances to feel better.… We’ve also had parents get deported and their kids left behind. All of those factors add up, and make it very, very difficult for someone to dig their way out of poverty.”

Fisher also said that more awareness needs to be brought to the issue. Since information about McKinney Vento does not always reach everyone, she has hung up flyers and notices about the rights of students without housing in public places.

“Education and awareness is always better,” Fisher said. “People need to know the resources that are available for them and the rights that are still available to them as students if they lose their housing. They should also know that we are here to help them and connect them to services. Integrity and privacy, however, are very important so that people aren’t embarrassed, so that their personal issues and if they lose housing are all kept as secret as possible.”

For a family or student to get back on their feet, it takes a combination of ways of helping depending on exactly what they need.

“Some people need to get hooked up with some money, through either rent assistance or a job,” Fisher said. “Others need money, a job and they need to address a health problem. Some, on top of that, might have to address a safety issue, substance abuse, or a mental illness that hasn’t been treated. You have to go through each problem one by one and address them as needed.…Sometimes it can just be having them reconnect or mend their relationship with an estranged family member.”

Childcare has also been a major cause of families losing their housing, especially in the pandemic. Due to schools reopening, the amount of childcare available has shrunk from five days a week for four to 11 year olds, to one day a week, because of limits on capacity.

“Under a regular school opening [before COVID-19], students who qualified for Project Extra Step were also given extended day and check in if they needed it, which was really awesome,” Fisher said. “From the time when the kids would go to school in the morning to extended day it would be from 7am to 6pm, so their parents would be able to keep a full time job. The pandemic has been brutal on families, because the childcare has not been adequate.”

Despite childcare being an issue, according to Fisher, there is no particular age or level of schooling that is the most common with the children that lose housing. In the past, she has helped preschool aged children enroll in preschools in Arlington through APS.

“On the other side of that age spectrum, we get much older kids who are not living with a parent or legal guardian, and they fall into the category of unaccompanied homeless youth,” Fisher said. “These can be children that immigrated here without their parents, and it depends on their housing set up. There are 18 year olds who might be kicked out of the house or choose to leave for certain reasons, and they will immediately qualify as well.”

If those students choose to apply to college, Fisher is also able to write a memo on their application. The memo would state that there would not have to be a parent or guardian signature on the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), or any other documentation involved in the process. According to Fisher, this makes the process easier.

“Graduating high school is achievable for unaccompanied homeless youth, as is applying to college.” Fisher said. “However, I’m not going to sugarcoat it, because it takes a lot of extra effort since they might not have the support at home to back them up. The school counselors still provide their usual services in terms of helping everyone with their course scheduling, helping them to choose what schools to apply to and what they might want to choose as a career. They could go into career tech training, to NOVA, or to a regular four year school, like George Mason or Virginia Tech.”

To receive this help, Fisher said that it is up to the student or someone close to them to bring it to a social worker’s attention. This can be a burden, but that it is necessary to access the resources that Project Extra Help can provide, as well as extra college help. This includes getting information about resources like SchoolHouse Connection, a catalog which describes how students can attend college while being without housing.

“Part of it is about paying for school, part of it is acquiring the tools you need like a laptop, clothing and bedding.” Fisher said. “The other part of it is what to do during vacations and school breaks, because everybody else goes home for Thanksgiving, but students who don’t have housing can’t. It’s a problem.”

The term ‘homeless’ is also one that peers should usually avoid using.

“‘Homeless’ conjures up an image,” Fisher said. “That isn’t what most people who have lost their house consider themselves as. The word has a negative connotation to it, and the people who lose their housing have absolutely nothing wrong with them, other than that they’ve had a series of unfortunate events happen to them. Instead, say ‘students who have experienced a loss of housing,’ and instead of ‘they became homeless,’ say ‘they had an unplanned move.’”

To help students who live in poverty and need food, many organizations are available for volunteering and donations, AFAC being one.

“At AFAC, we supply families with 40 pounds of food each week,” Jolie Smith, Director of Development at AFAC said. “Six percent of our funding comes from the government, but the rest is for us to raise, and our team has raised 3.7 million dollars every year. It’s a big number, but that amount of money helps to feed over 2,400 families on a weekly basis.”

Smith and her team are in charge of fundraising at AFAC, which according to Smith, along with volunteering, has become even more important since the COVID-19 pandemic began.

“We’ve seen a 50 percent increase since COVID[-19] started in the number of families we’ve been serving, and at any given time we could have that number double,” Smith said. “Our donors have been so generous during COVID[-19]…, and we get a lot of money and food donations, but we absolutely need our volunteers to help us run AFAC.”

Thirty percent of the food bank’s clients are elderly, and 35 percent of them are children, but none are identified as without housing.

“Our families are not homeless, but they are just a step above being homeless,” Smith said. “If they are homeless, then we would refer them to resources that are specifically for those who have lost their housing.”

In order to receive assistance from AFAC, a referral is required.

“We want to make sure that we’re reaching the people that are truly really in need, so we find people through the county, and sometimes churches,” Smith said. “If you’re coming to receive services from us, there are also probably other services that you would benefit from. We want to make sure that they’re checking in with the social workers in the county, so that they can get all of the services available.”

According to Smith, the organization’s services can help to prevent individuals from losing their housing.

“If you or your kids are hungry, I couldn’t imagine anything worse,” Smith said. “When you’re hungry, it’s just debilitating. When we supply them with 40 pounds of food a week, we are taking that piece of stress away from families, and it’s a big supplement to their food budget. Then they can use that money for medications or rent, and focus on getting a better paying job or the health care that they need.”

Over the past year, volunteers have donated over 50,000 hours to AFAC.

“We have over 2,000 volunteers who help us throughout the year,” Smith said. “If you’re 14 years or older, you can come in with a group or just by yourself… We also have a summer internship program for teens.”

Karush, who has been volunteering for over a decade, started out with her family.

“AFAC did and still does a good job of incorporating families into volunteering and showing kids the importance of giving back to your community,” Karush said. “My family and I started bagging food once a month, which was pretty low commitment. My mom decided to take on the role of bagging coordinator for my elementary school, which she’s still doing today. That was an opportunity for us to continue volunteering as we got older… and it was important for my mom to show to other families in Arlington what AFAC is and why it’s important.”

Karush’s favorite part of volunteering has been bagging.

“Oftentimes, I get to do it with my mom’s elementary school bagging group, and explain why what they’re doing is important and help them get excited to come back, which is really meaningful.”

Once she got older, Karush wanted to spread the word of AFAC and its importance further.

“When I got to high school, I created a bagging group for W-L students,” Karush said. “That was just me, without my family, and the main thing that we did was volunteer at AFAC twice a month. I would send out a sign up link, and we would normally spend about two hours there, mostly bagging.”

The group had the desired effect.

“In the beginning, a lot of my peers didn’t know much about AFAC and the high demand that it’s in,” Karush said. “Volunteering, I think, has shown that sometimes the biggest difference starts on the smallest level. For instance, if you bag oranges for two hours with a group of ten people, you can get through 20 crates or so of oranges. That can supply AFAC with enough oranges to give out for maybe a week or two. It really shows that everything you do can have such a direct relation to a positive action in the world, or somebody getting an extra piece of food to eat, which is why it’s so important.”

One member of Karush’s group, senior Ali Obenberger, took it one step further for her Creativity, Activity, Service (CAS) project.

“For her project, she decided to do a virtual 5k to raise money for AFAC, and she raised over 10,000 dollars,” Karush said. “It was amazing to see someone who had started out in my group develop a passion of their own and do so much with it.”

Some, unlike Karush and Obenberger, can be skeptical about volunteering.

“If you tend to live in your own bubble, you might think that you come in to volunteer and people are drugged out or drunk, or something like that, and that’s not the case,” Smith said. “It’s just families that need help and support. Interacting with our clients, to me, is the best part of volunteering. If someone was intimidated, they could always come in and tour the facility so that they could feel more comfortable.”

Karush would agree.

“Anyone who is considering volunteering at AFAC should go for it,” Karush said. “It’s a very happy place to volunteer at; it’s people getting together to do what they can to make a change in the community. It can be a little intimidating at first, if you show up without knowing anyone, but you can always bring a friend. The first step is the hardest step to take, so once you’ve done that it’ll be easier for you to become more involved.”

One volunteer role, known as distribution, according to Karush, however, can be emotional. Distribution often involves helping people find what they need for food, and clarifying what they can and should take.

“Clients at AFAC can oftentimes feel embarrassed, and it can be hard to know how to handle the situation, because you don’t want to offend anyone,” Karush said. “Sometimes people will want more food, and it’s difficult to deal with because you want to give them as much as possible, but there’s protocols to make sure that everyone has access to the same amount of food. It’s hard to see how stressful food can be for people, and that’s why organizations like AFAC are so important.”

Distribution also helped to put things further into perspective for Karush.

“You spend all this time bagging vegetables and cans, and then when you go to distribution, you see people that are just like your neighbors,” Karush said. “When you’re bagging groceries, it’s really easy to feel like a savior, but you aren’t one. The cost of living in Arlington is just really high, and sometimes an income isn’t good enough to pay for everything… By volunteering, you’re doing for your neighbors what you’d want them to do for you.”

Due to the pandemic, Karush has been volunteering by holding food drives instead, another way to give to AFAC. Despite the help that they receive, AFAC always is in need of more support from the community.

“AFAC needs money donated, food donations, and volunteers,” Smith said. “All three of those we need, and that will never go away.”

The process to sign up to volunteer is also one that is simpler than some might think.

“To volunteer, just go to the website and register, or email volunteer services, which is listed on the website.” Smith said. “I’m also happy to help anyone out that would want to volunteer, so someone can email me at [email protected].”

According to everyone interviewed, anyone can help. When Fisher was asked about why she made the decision to become a homeless liaison, she said this:

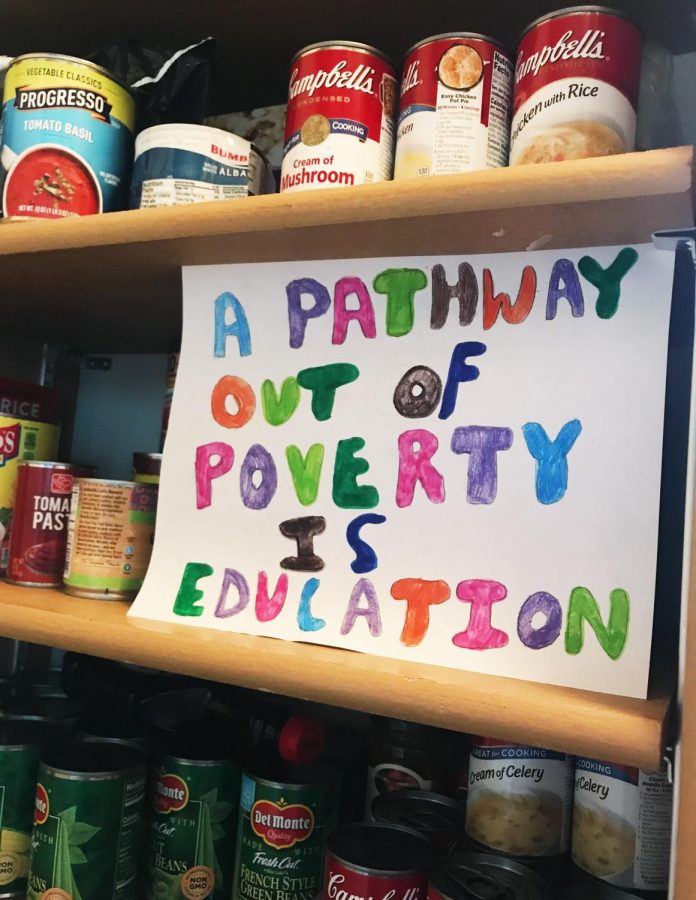

“A pathway out of poverty is education.”