Sophomore diagnoses medical mystery patient

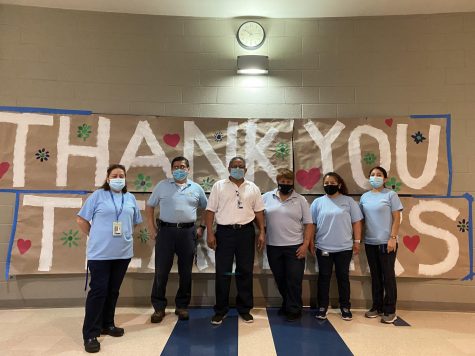

Sophomore Alana McBride is greeted by stormtroopers during one long January stay in the hospital. McBride was later inspired to volunteer in patient care at Inova Fairfax Medical Campus, doing the same job others had done for her.

Sophomore Alana McBride has a patient.

She has several, actually. She considers every person she comforts and delivers flowers to in her job at Inova Fairfax Medical Campus to be a patient of hers. However, one patient is unique because McBride was able to diagnose her when 35 other doctors could not.

She knew what her patient’s diagnosis was because last July, she, too, was diagnosed with Functional Neurological Symptom Disorder (FND).

According to the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD), FND is a neurological disorder wherein the nervous system experiences complications in the sending and receiving of messages to the body. It is a broad diagnosis for a large range of symptoms.

McBride started noticing her own symptoms in January of 2018. “I lost most of my muscle functioning in the left side,” McBride said. “I started using a cane, being in the hospital and going to different doctor’s appointments all the time. [It was] difficult to move my arms and legs, and my face had started to [droop].”

When her symptoms first started, she thought very little of them. “I first started experiencing symptoms late December 2017, early January, and I wasn’t highly concerned,” McBride said. “I just thought, ‘Oh, my arm hurts a little bit, I can’t move it as well, I just have just pulled a muscle.’ My legs felt a little weird but I thought, ‘Oh, I do ballet, I just pulled a muscle.’”

Soon, she realized the situation was more serious. “On January 15, I had the last ballet class I’ve had in my life because I could not walk after it,” McBride said. “That’s when I realized we actually needed to do something. And my mom agreed, because I couldn’t move my left hand, and my face started to droop.”

Even still, when McBride and her mother finally were checked into the emergency room, they did not expect much. Much to her surprise, she was admitted for a long period of time. “I really had a lot of optimism at first because I hadn’t experienced something that was really big, medically,” McBride said. “It was the first time I was terrified for a medical reason. And rightly so, as someone who was young and healthy, and then was suddenly not. I had a difficult time processing it because I thought this didn’t happen to fourteen-year-olds. Fourteen-year-olds don’t lose muscle function all of a sudden.”

After that, the road to diagnosis was long and tiring. McBride said she went to too many appointments to remember, with rheumatologists to neurologists to anesthesiologists, and had six Magnetic Resonance Imagings (MRIs) and several blood tests with no answers.

“My frustration in this whole process was how many times we had to go back to get MRIs because they just would do one piece at a time,” McBride’s mother, Jennifer McBride, said. “We had multiple MRIs there, as they worked their way through, then they did the vertebrae, then they did her spine, and I [thought] ‘Why couldn’t we have just done this the first time we were in the machine?’ She still was in pain, and it was hard to see her in so much pain. And then they gave her these drugs, and they were giving her side effects.”

The scariest part for both McBride and her mother was the uncertainty of not having a diagnosis for those first six months or so. “Not knowing [what it is] when it’s something medical is terrifying,” the younger McBride said. “It’s scary to not know why you can’t walk correctly or why you can’t use your hands, or why your face is weird. It’s scary not knowing.”

McBride has two younger siblings, a sister in seventh grade and a brother in third grade. The two were not made aware of the details of McBride’s symptoms until later into the process. “When I was admitted to the hospital, my siblings both realized, ‘Okay, Alana’s sick,’” McBride said. “They both could register that. But, they are younger, so my family (my mom, my dad, and I) kept my siblings as out of the loop as possible because we wanted to pretend like everything was okay. In April, when some of the doctors started mentioning things like ALS [amyotrophic lateral sclerosis] or muscular dystrophy, that’s when my siblings would overhear stuff, and they got worried. They asked a few questions and we just tried to reassure them.”

Finally, in July, McBride was diagnosed with FND. To cope, she began volunteering at the Inova hospital in Fairfax on weekends to give back and took up researching her condition for hours at a time. While doing that research, she stumbled across a story in the New York Times about medical mysteries that contained a case that showed symptoms similar to hers. Though the patient had seen 35 doctors and not one had diagnosed her, after looking over her MRIs and blood tests, McBride knew exactly what was wrong with her; although she had some different symptoms than McBride, she had FND. McBride was so confident, she emailed the writers with her hypothesis.

“I knew the woman hadn’t been diagnosed, and she was looking for help,” McBride said. “I thought I could help her. I had to suffer through months and months of not knowing, and being scared, and I didn’t want this woman to go through any more of that.”

Soon after, she got an email back. It was from Associate Producer Emma Moley, producer of a collaboration between Netflix and the New York Times to create a show looking at medical mysteries, and the woman McBride diagnosed would be one of the cases. They were impressed by her confidence in her knowledge and interested in her similar symptoms, so they asked to interview her. She did a Skype interview, two phone interviews, and in February of this year, they told her they wanted to put her on a train to New Haven, Connecticut, so she could meet her patient and everybody who was working on the series.

“When I got the first email back, I was at the hospital volunteering, and I was with one of my co-workers,” McBride said. “I was like, ‘Elly, look at this!’ And she was like, ‘Oh my gosh!’ I was kind of freaking out, but I had to keep it on the down-low because I was still working. I thought, whoa, I just helped this woman, and I can continue to do that. I was just so excited.”

Junior Elly Loyd is a student at George Mason High School and was the coworker McBride was with when she found out about the show.

“Out of nowhere, she said she was going on this trip with the New York Times, and I was like, ‘Okay, explain?’” Loyd said. “It was kind of incredible. I said, ‘so you’re 15 years old and you’re diagnosing people with the same thing you went through.’ She was in shock and awe. She seemed very proud of herself.”

It was not until the trip in February that the producers confirmed her diagnosis had been correct. She was able to tell her patient about her treatment options, but she ran into some difficulties she was very much familiar with. MRIs and Electroencephalography (EEG) tests are typically normal in a person with FND. Because of this, according to NORD, in the past FND has been ignored by health care professionals, and it was believed to be a purely psychological disorder until the last decade. Therefore, McBride says it can be a difficult diagnosis to have.

“My patient didn’t want to accept her situation,” McBride said. “That was a really strange situation, because she wanted to know what was wrong with her, but she didn’t want this diagnosis, because a lot of doctors will just say, ‘You’re crazy’, or ‘It’s all in your head.’ So, there’s a lot of scary things with this diagnosis. I was told by one doctor that it was all in my head, and I went home after that appointment and I cried. I knew that I wasn’t faking, I was like, why did a doctor tell me that? I’m not doing anything. It angered me.”

McBride’s mother said that things moved pretty quickly once the producers said they wanted to meet her. “When they wanted to talk with her, I said, ‘Great, but first things first, you must tell them you’re a fifteen-year-old high school student,’” the elder McBride said. “So she did, and they were like, ‘We’ll still talk to you.’”

Once she arrived, McBride’s age continued to impress and confuse those around her. “At first they thought I was a college student,” McBride said. “I told them I was 15, a sophomore, and they thought that was cool. Most of the people that have worked on the docu-series have been impressed. They’ve said, ‘you’re so young, you’ve been through so much, but you know a lot.’”

McBride says she thinks despite her age, she has been through things that should not be discounted just because she is 15. “I thought for a few months that I was going to die,” McBride said. “That gives you a whole new perspective on life. Being scared does that. I was like, yes, I know I’m 15. I’m very much a child. But I do have the knowledge that a lot of adults don’t.”

Now, McBride’s interview may be put into the untitled documentary series, she has successfully diagnosed a previously undiagnosable patient, and though she is still on lots of medication, she is doing much better with her condition than she was last year, and her only remaining symptoms are occasional twitches.

“It’s weird having diagnosed someone,” McBride said. “I’m 15, I don’t want to be a doctor, I’m just trying to live my life and not be sick. Then I stumble upon this, and some crazy stuff happens.”